Two Dilemmas: One False, One Real

Addressing Euthyphro and Naturalist Morality

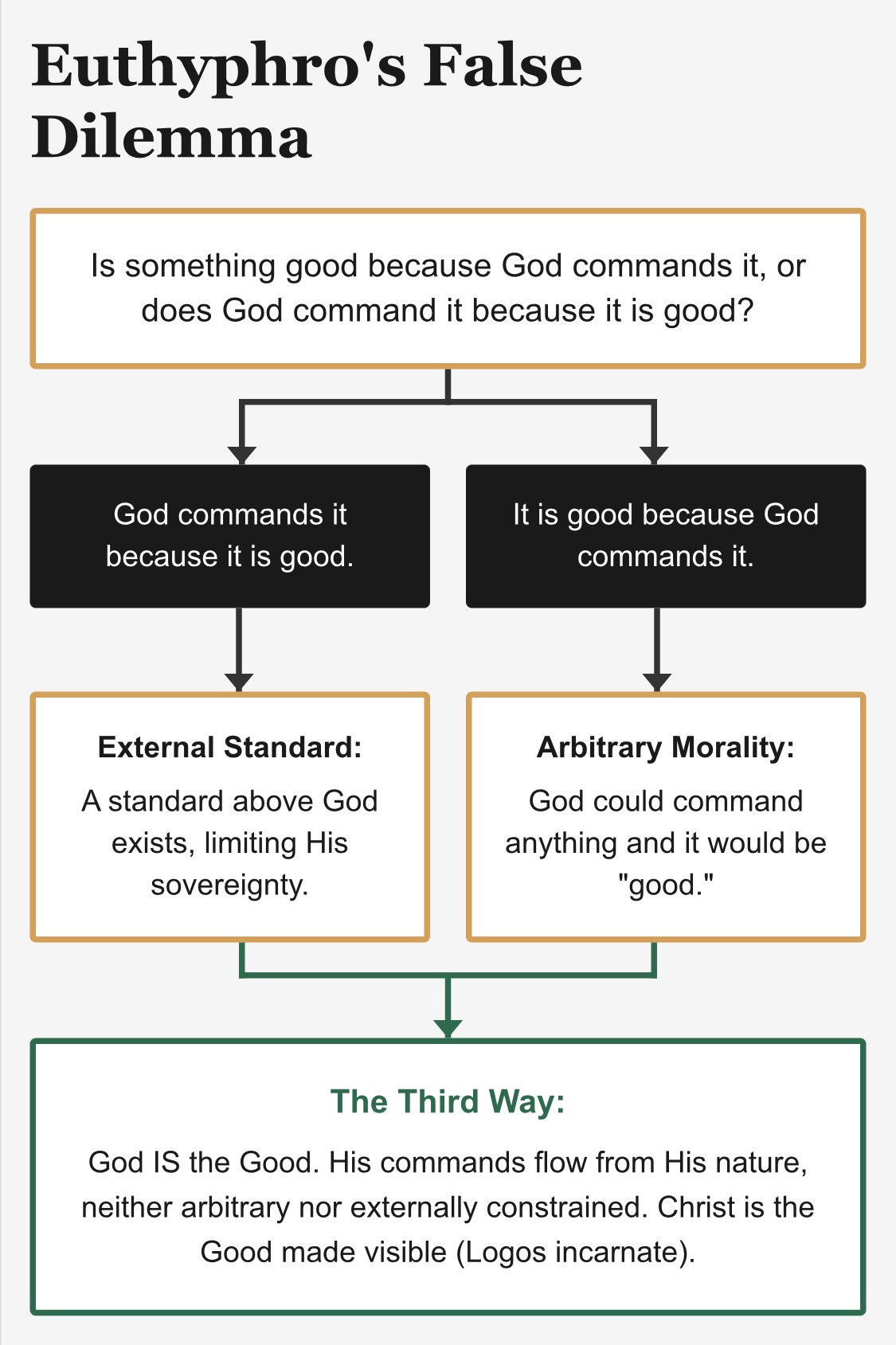

For over two millennia, the Euthyphro dilemma has been deployed against Christian theistic ethics. The argument seems devastating: either God commands things because they are good (in which case goodness is independent of God), or things are good because God commands them (in which case morality is arbitrary). The Christian theist, so the story goes, is trapped.

But there’s an irony here. The Euthyphro dilemma rests on a false dichotomy, and Christians have had a coherent escape route since at least Augustine. Meanwhile, a structurally identical dilemma confronts the naturalist, and this one has no exit.

The Euthyphro Dilemma

Socrates poses the question to Euthyphro regarding the gods: “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?” Translated into Christian terms: Is something good because God commands it, or does God command it because it is good?

The first horn suggests that goodness exists independently of God, as an external standard He merely recognizes. This seems to limit divine sovereignty. The second horn makes morality arbitrary: if “good” just means “whatever God commands,” then God could command evil and it would become good by definition.

Both options seem unpalatable. But notice the hidden assumption: the dilemma presupposes that God and the Good are two separate things that must be related somehow. What if they aren’t?

The Third Way

The classical Christian answer, developed by Augustine, Aquinas, and others, is that God does not conform to an external standard, nor does He arbitrarily create moral facts. Rather, God is the Good. Goodness is identical with the divine nature.

On this view, God’s commands flow necessarily from what He is. He cannot command evil, not because some external law prohibits it, but because evil is contrary to His nature. The Good is not above God (first horn) nor beneath God’s arbitrary will (second horn). The Good is God, and His commands are expressions of His character.

Christianity adds a further specification: the character of God is not an abstraction. It is made visible in Christ. The Logos, the rational and moral structure of reality, became incarnate. We do not have to guess what goodness looks like; we have seen it walking around in first-century Palestine, touching lepers and confronting hypocrites.

The Euthyphro dilemma, then, is a false dilemma. It offers two options while ignoring a third that dissolves the problem entirely.

The Naturalist’s Dilemma

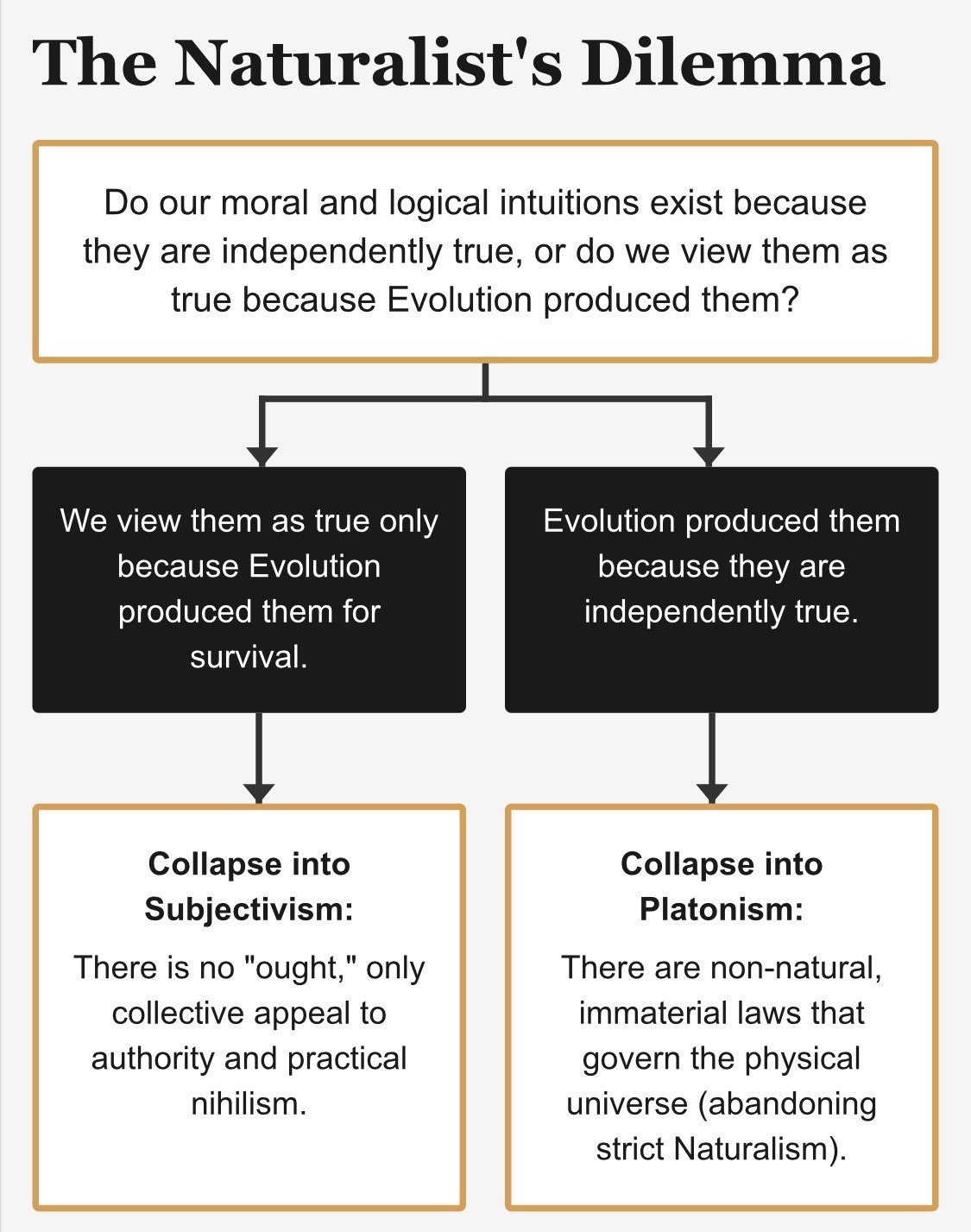

Now consider a parallel question directed at the naturalist: Do our moral and logical intuitions exist because they are independently true, or do we view them as true because evolution produced them?

This is not a hypothetical. Evolutionary debunking arguments are a live issue in metaethics. Thinkers like Sharon Street and Michael Ruse have pressed exactly this point. If natural selection shaped our moral sense, what does that imply about its reliability?

The naturalist faces two paths.

Path One: We view them as true because evolution produced them. On this horn, our sense that evil is wrong and modus ponens is valid are products of selective pressure. They exist because they enhanced survival, not because they track anything real. Ruse is frank about the implication: morality is “an illusion foisted on us by our genes.”

But if moral intuitions are survival-enhancing illusions, the same applies to logical intuitions. The felt necessity of basic inference rules becomes just another trick of the nervous system. There is no “ought,” only the biological appearance of one. This collapses into subjectivism, where normativity reduces to collective sentiment and practical nihilism follows. “We disapprove” replaces “this is wrong.”

Path Two: Evolution produced them because they are independently true. On this horn, natural selection somehow latched onto pre-existing, mind-independent moral and logical truths. Our intuitions are reliable because evolution tracked the normative structure of reality.

But what is this normative structure? Where do these truths reside? They are not physical objects. They are not located in space and time. They cannot be detected by scientific instruments. The naturalist who takes this path has posited immaterial, non-natural laws that govern the physical universe. This is Platonism, and it abandons the core commitment of naturalism: that the physical world is all there is.

The Asymmetry

Here is the critical difference between the two dilemmas. The Euthyphro dilemma has a third option that dissolves the problem. The Naturalist’s Dilemma does not.

The Christian can say: God is the Good, and Christ is the Good made visible. This is not an ad hoc escape; it follows from the doctrine of divine simplicity and the Incarnation, both of which predate the modern formulation of the dilemma by centuries.

The naturalist has no analogous move. There is no third option where Nature is the normative, because naturalism defines nature as non-normative. The physical world, described by physics, contains no “oughts.” If oughts are real, they cannot be natural (abandoning naturalism). If oughts are not real, normativity is an illusion (abandoning the authority of reason and morality).

The naturalist wants the authority of the right path while maintaining the ontology of the left. Science and logic are reallyvalid! Evil is really wrong! But there is only matter in motion, and matter in motion does not generate binding norms.

Why No Third Way for Naturalism

The claim that naturalism cannot have a third way is not merely an observation; it is a logical impossibility rooted in the structure of naturalism itself. Two classical arguments from David Hume and G.E. Moore make this explicit.

The Is-Ought Gap

The primary contradiction lies in attempting to derive a prescriptive conclusion (what you ought to do) from purely descriptive premises (what is happening in nature).

Naturalism’s limit is this: science can describe that a mother protects her young (biological fact). It can explain why she does it (evolutionary instinct). What science cannot output is the sentence “She ought to protect her young.”

To say “she ought to” is a natural fact is to claim that a physical arrangement of atoms contains a command. But atoms do not issue commands; they simply move.

Hume identified this problem in 1739: “I have found that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning... when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not.”

The gap between “is” and “ought” cannot be bridged by adding more “is” statements. No accumulation of descriptive facts yields a prescription.

The Open Question Argument

In 1903, G.E. Moore formalized this objection with what he called the “naturalistic fallacy.”

If “Good” were synonymous with a natural property like “pleasure” or “survival,” then asking “Is pleasure good?” would be a tautology, equivalent to asking “Is a bachelor an unmarried man?” But consider: a naturalist claims that goodness is identical to evolutionary survival. We can then meaningfully ask, “I know this behavior helps us survive, but is it good?” (for example, eliminating a rival group). Because the question makes sense, because it remains genuinely open, “Good” cannot be identical to “Survival.”

Treating “Good” as a natural object is therefore a category error. Goodness is a non-natural property. If you drag it down into nature, you destroy it by reducing it to mere biology. If you leave it outside nature, you abandon naturalism.

The Failure of Naturalistic Identity Claims

Contemporary ethical naturalists, such as the Cornell Realists, attempt to mimic the Christian solution. They argue that goodness is identical to human flourishing, just as water is identical to H2O.

But this analogy fails precisely where it matters. “Water = H2O” is a reduction of one physical thing to another physical thing. Both fit within a naturalistic universe. “Good = Flourishing” attempts to reduce a moral obligation to a physical state. These are different categories.

If “Good” just means “Flourishing,” then the sentence “You ought to seek the good” translates to “You ought to seek flourishing.” But why ought you seek flourishing? If you answer “Because it is good,” you are arguing in a circle. If you answer “There is no ‘why,’ it is just a biological drive,” you have collapsed into subjectivism and the left horn of the dilemma.

The Christian identity claim (God is the Good) works because both terms occupy the same ontological category: the necessary, self-existent ground of reality. The naturalist identity claim fails because it tries to equate a normative property with a descriptive state. It is the claim that a stone can believe.

Conclusion

The Euthyphro dilemma is a false dilemma. It has rhetorical power against a certain conception of Christian theism, one where God is an agent separate from the Good who must either obey or create moral facts. Classical Christian theism does not fit this picture. The dilemma’s force depends on ignoring the mainstream theological tradition.

The Naturalist’s Dilemma is a real dilemma. Both horns lead to conclusions the naturalist cannot accept. Subjectivism evacuates the authority of reason and morality. Platonism contradicts naturalism itself. And there is no third way, because the very categories of naturalism preclude it.

The person wielding Euthyphro against the Christian might consider whether their own position can survive the same structural challenge. The question is not just “Can Christian theism ground morality?” but “Can anything else?”