The Load-Bearing Joint of Evolution: Why Naturalists Avoid Abiogenesis

There’s a rhetorical move that shows up constantly in origins debates. Someone will say, “I’m not here to discuss abiogenesis,” then immediately cite amino acids on asteroids as evidence that protein assembly was “pretty likely.” That’s not bracketing the question. That’s answering it while pretending not to.

And the answer doesn’t actually help.

Nobody doubted amino acid availability. Miller produced them in 1953. The asteroid findings are genuinely interesting, but they don’t touch the real problem. The gap between “amino acids exist” and “functional proteins exist” is the question.

After seventy years of research, the best evidence for abiogenesis is still “we found building blocks.” That’s like explaining the origin of a library by pointing to trees. The raw materials aren’t the question. The specified information is.

And it’s not one problem. It’s a series of them, each requiring its own probabilistic miracle.

You need amino acids. Fine, you have those. But you need them homochiral, all left-handed, because mixed chirality doesn’t fold properly. Prebiotic chemistry produces racemic mixtures. That’s problem one.

You need polymerization, but peptide bond formation is thermodynamically unfavorable in aqueous solution. Water is the enemy of the reaction you need water to host. That’s problem two.

You need not just any polymer but a specific sequence. The functional fraction of sequence space is vanishingly small. That’s problem three, and it’s the one Axe quantified.

You need that protein to do something useful in isolation, which means you need it to fold correctly, which depends on the sequence you don’t yet have a mechanism to specify. That’s problem four.

You need a lipid membrane to concentrate reactants and maintain disequilibrium, but membranes require their own specialized synthesis. That’s problem five.

You need information storage, which means nucleic acids, which have their own synthesis problems, their own chirality requirements, and their own sequence space issues. That’s problem six.

You need the code, the mapping between nucleotide triplets and amino acids. That mapping is arbitrary, not chemically determined. It requires the very translation machinery it encodes. That’s problem seven, and it’s circular.

Each of these problems is independent. Solving one doesn’t help with the others. They all have to be solved simultaneously in the same location at the same time for any of them to matter.

This isn’t a gap. It’s a chasm with no bottom.

Here’s why you can’t actually bracket abiogenesis, even if you want to.

The evolutionary narrative is a causal chain: cosmic to chemical to biological to complex. Natural selection does the heavy lifting in the story, but selection requires replication. Replication requires functional molecular machinery. Functional machinery requires specified sequences. The chemistry-to-biology transition has to deliver those specified sequences without selection, because selection isn’t operating yet. There’s nothing for it to select. You need a self-replicating system before differential reproduction means anything.

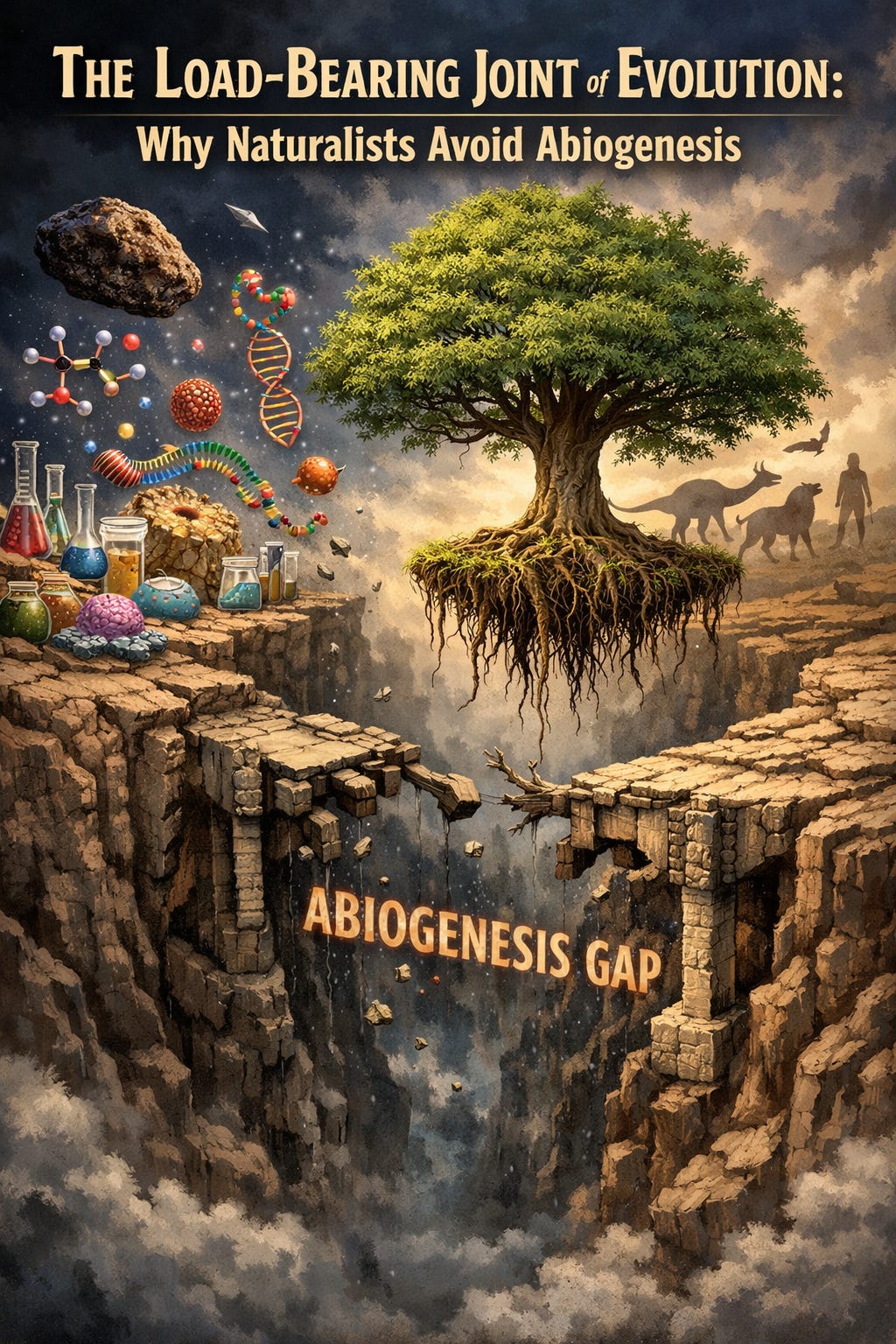

That’s the lynchpin. If that bridge doesn’t hold, everything downstream is suspended in midair.

Think about what’s being asked. The naturalist needs unguided chemistry to produce, at minimum, a self-replicating molecule with the fidelity to sustain selection. Not eventually. First. Before any evolutionary mechanism can begin operating.

The RNA World hypothesis was supposed to solve this by positing a simpler replicator. But ribozymes face the same sequence space problem proteins do. And RNA is less stable than DNA, harder to synthesize prebiotically, and requires its own specialized chemistry. You haven’t simplified the problem. You’ve relocated it.

Every proposed solution follows the same pattern: push the information problem back one step and declare victory. But the problem doesn’t disappear by moving. It waits.

This matters because “evolution” is often treated as a complete explanation for biological complexity. But evolution, properly defined, is differential reproduction with heritable variation. It explains how existing replicators change over time. It does not, and cannot, explain how replicators originated. That’s a different question requiring a different answer.

You can’t demonstrate that evolution explains biological history by assuming the one transition that makes evolution possible. That’s not evidence. That’s the conclusion dressed up as a premise.

So no, abiogenesis isn’t “to the side.” It isn’t a separate research program that biologists can politely ignore while discussing common descent. It’s the load-bearing joint in the entire framework.

If unguided chemistry cannot, even in principle, produce specified sequences sufficient for self-replication, then the naturalistic tree of life has no roots. You can describe the branches in exquisite detail. You can map every twig. But the tree is floating.

And floating trees don’t grow.

This is a real problem for naturalistic evolution. It's obvious that biological things have the "fingerprints" of directed information. This conclusion is not based on what we don't know, (gap) but on what we do know. It is contrary to our experience that the complexity of life, even first life can arise from undirected physics and chemistry alone.