The Atheistic Sleight of Hand: Redefining Terms for Historic Disassociation and Rhetorical Benefit

Setting the record straight

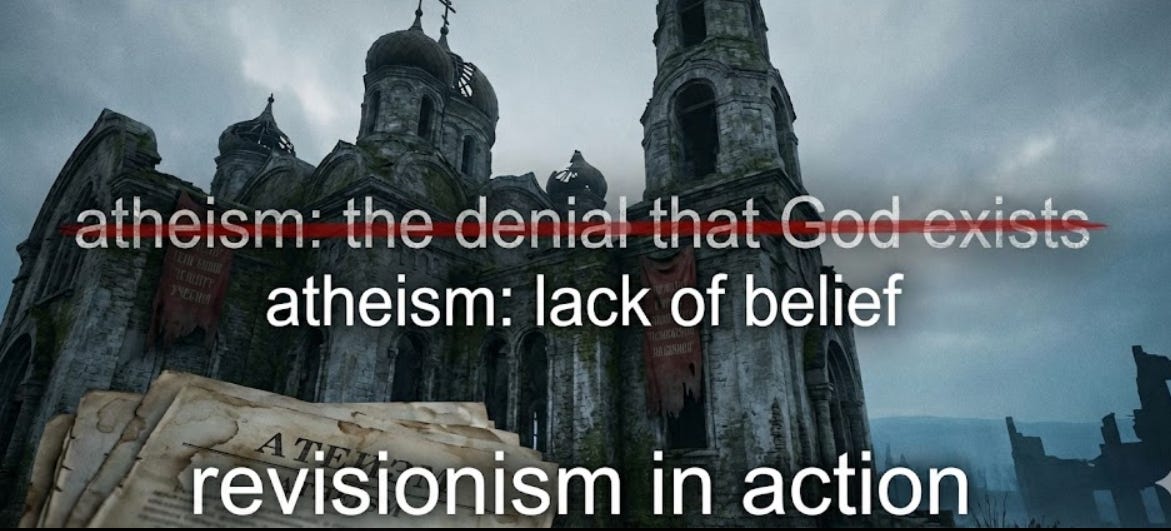

Ask a contemporary atheist what atheism means, and you’ll likely hear: “It’s just a lack of belief in God.” This definition has become standard in online debates, activist circles, and even some academic discussions. It’s presented as neutral, obvious, even definitional.

It’s also historically false.

For most of history—from ancient Greece through the Enlightenment and into the 20th century—atheism meant something quite different: the positive claim that no gods exist. It was a thesis about reality, not a psychological state. When d’Holbach wrote The System of Nature or Bertrand Russell delivered “Why I Am Not a Christian,” they weren’t describing absence of belief. They were arguing for materialism and naturalism, defending comprehensive worldviews that denied supernatural reality.

So what changed? Why did atheism get redefined from a substantive metaphysical position to a mere lack of belief?

The answer is strategic. The psychological definition serves three crucial functions: it evades the burden of proof, it conceals atheism’s substantive commitments to materialism and naturalism, and most importantly, it enables contemporary atheists to distance themselves from atheism’s 20th-century embodiments.

That last point deserves emphasis, because the 20th century is precisely what modern atheists need to forget.

When Atheism Had Power

The 20th century witnessed something unprecedented: explicitly atheist states that enshrined atheism in law, propagated it through mandatory education, and enforced it through systematic violence. These weren’t regimes that merely happened to be atheist. They made atheism central to their identity and program.

The Soviet Union

The USSR didn’t just tolerate atheism; it institutionalized “scientific atheism” as official doctrine. Beginning in 1959, “The Foundations of Scientific Atheism” became mandatory coursework in Soviet higher education, with the explicit goal of producing a “scientific-materialist (i.e. atheistic)” worldview (Wikipedia, 2024b). The League of Militant Atheists reached 5 million members. Departments of Scientific Atheism were established in universities.

And then came the persecution.

During Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937-1938, over 30,000 “church people” were arrested in just four months—including 166 bishops, over 9,000 priests, over 2,000 monks, and nearly 20,000 lay believers. Half the clergy were executed immediately; the rest were sent to the gulag (Christian History Magazine, n.d.). By 1939, of approximately 54,000 Orthodox churches operating in 1917, fewer than 500 remained open (EBSCO Research Starters, n.d.).

The final tally: 200,000 Orthodox priests, monks, and nuns killed during the Soviet period, confirmed by the Russian state commissioner in 1995 (Wikipedia, 2024d). Other estimates place it at 600 bishops, 40,000 priests, and 120,000 monks and nuns (Acton Institute, 2008).

Albania

Enver Hoxha went further. In 1967, Albania became the world’s first constitutionally atheist state. Every single one of Albania’s 2,169 religious buildings—every church, every mosque, every monastery—was closed or destroyed (Wikipedia, 2024f). The 1976 Constitution stated explicitly:

“The state recognizes no religion whatever and supports atheistic propaganda for the purpose of implanting the scientific materialistic world outlook in people” (Article 37).

Religious practice wasn’t merely discouraged. It was criminalized. The 1977 Criminal Code prescribed three to ten years in prison—or death—for “religious propaganda and the production, distribution, or storage of religious literature” (Wikipedia, 2024f).

Over 2,000 clergy and believers were imprisoned, tortured, or executed between 1945 and 1985 (Irreligion in Albania, 2024). Father Ernest Simoni Troshani spent 28 years in prison for holding a mass in memory of President Kennedy (Balkan Insight, 2019). Father Ndoc Luli was sentenced to death in 1980 for baptizing twins (ONE Magazine, 2024). Bishop Franco Gjini was tortured with electric shocks and wooden splinters under his fingernails before being executed in a muddy ditch with eighteen others (ONE Magazine, 2024).

Cambodia

Under Pol Pot’s “ardent Marxist atheist” regime, Cambodia experienced what scholars describe as persecution “only matched in severity by the persecution of religion in Albania and North Korea” (Wikipedia, 2024h).

Before the Khmer Rouge took power, Cambodia had between 65,000 and 80,000 Buddhist monks. By the time of Buddhist restoration in the early 1980s, fewer than 3,000 remained worldwide (Wikipedia, 2024i). Up to 50,000 monks were massacred. 95% of Buddhist temples were destroyed (Aegis Trust, 2020).

Monks were regarded as “social parasites,” defrocked, and forced into labor brigades. Many were executed. Temples became storehouses and jails. Images of the Buddha were defaced and dumped into rivers. People caught praying were often killed (Facts and Details, n.d.).

The overall death toll: 1.5 to 2 million people—25% of Cambodia’s entire population—killed between 1975 and 1979 (Wikipedia, 2024h).

China

Mao’s Cultural Revolution designated religion as one of the “Four Olds” to be destroyed. In Tibet alone, all but 11 of 6,200 monasteries were destroyed (Wikipedia, 2024j). Thousands of monks and nuns were imprisoned. Sacred texts were burned. Many Tibetan Buddhists were forced at gunpoint to participate in destroying their own monasteries (Wikipedia, 2024k).

Across China, hundreds of thousands of temples were obliterated—what one scholar called “an immense wave of auto-cultural genocide” (University of Notre Dame, n.d.). Marxist propaganda depicted Buddhism as superstition and religion as “a means of hostile foreign infiltration” (Wikipedia, 2024k).

What These Regimes Said About Themselves

Here’s what matters: these regimes didn’t claim to be merely “lacking belief in God.” They explicitly identified as atheist. They codified atheism in their constitutions. They created official institutions to propagate atheism. They made atheism mandatory curriculum.

And they were clear about what atheism meant.

Lenin stated it directly: “Religion is the opium of the people—this dictum by Marx is the corner-stone of the whole Marxist outlook on religion” (Wikipedia, 2024e). Not “we happen to lack belief.” Not “we’re neutral on the God question.” But: religion is false consciousness, an obstacle to progress, to be eliminated.

Albania’s Constitution didn’t say “the state is agnostic.” It said the state “supports atheistic propaganda for the purpose of implanting the scientific materialistic world outlook.” That’s atheism as doctrine, worldview, and program.

The Khmer Rouge’s 1976 Constitution explicitly forbade “all reactionary religions that are detrimental to Democratic Kampuchea” (Facts and Details, n.d.). This wasn’t incidental. It was ideological.

When atheism achieved political power, gained institutional embodiment, and operated without opposition, it consistently allied itself with scientific materialism, opposed religion as false and harmful, and sought to eliminate religious practice and belief through state force.

The Modern Dissociation

Now watch what happens when you raise this history with contemporary atheists.

“But atheism is just lack of belief—it can’t cause anything.”

“Those regimes were about totalitarianism, not atheism.”

“That was communist atheism, not real atheism.”

“You can’t judge atheism by its worst adherents.”

Notice the pattern? Every response denies that the 20th century tells us anything about atheism. Soviet scientific atheism? Not real atheism. Albanian constitutional atheism? Not real atheism. The systematic massacre of 50,000 Buddhist monks by an “ardent Marxist atheist” regime? Nothing to do with atheism.

This is where the “lack of belief” definition becomes essential. If atheism is merely a psychological state with no content, then:

Soviet atheism has nothing to do with “atheism as such”

You can say “that wasn’t about atheism, that was about communism”

The 20th century becomes irrelevant

Contemporary atheists bear no burden to explain or account for any of it

The psychological definition doesn’t just shift the burden of proof. It rewrites history.

Why This Is Revisionism

When Soviet universities taught “The Foundations of Scientific Atheism,” they weren’t teaching students to “lack belief.” They were teaching dialectical materialism, the denial of supernatural reality, and the theory that religion is false consciousness to be overcome (Wikipedia, 2024b).

When Albania mandated “atheistic propaganda” to instill “the scientific materialistic world outlook,” it wasn’t describing a psychological absence. It was describing a comprehensive metaphysical doctrine the state was obligated to propagate.

When the Khmer Rouge massacred monks and destroyed temples, they were acting on substantive atheist convictions about reality and the harmfulness of religion.

To claim this history is irrelevant to evaluating atheism requires denying what atheism meant in these contexts. And what it meant is documented in their own words.

Contemporary atheists insist: “That wasn’t atheism; that was something else that happened to coincide with non-belief in God.”

But the Albanian Constitution didn’t say “the state recognizes the psychological absence of theistic belief.” It said “the state recognizes no religion whatever and supports atheistic propaganda for the purpose of implanting the scientific materialistic world outlook in people.”

That’s not coincidence. That’s atheism as these regimes understood it, taught it, codified it, and enforced it.

Addressing the Excuses

“Religious regimes have also committed atrocities.”

True. But this is deflection, not argument. The question isn’t whether religious people have done evil—they have. The question is whether atheism functions as a substantive worldview with real consequences. The 20th century answers: yes.

Moreover, there’s an asymmetry. When Christians launched Crusades, they violated core Christian principles: “love your enemies,” “turn the other cheek,” “blessed are the peacemakers.” When Soviet atheists destroyed churches and killed clergy, they were following their principles: if religion is false consciousness that harms human flourishing, eliminating it is rational and beneficial.

“Totalitarianism was the problem, not atheism.”

Then why were these totalitarian regimes so uniformly atheist? Why did they invest enormous resources in atheist propaganda, establish departments of scientific atheism, and create organizations like the League of Militant Atheists if atheism was incidental?

Because Marxist-Leninist ideology required atheism. Religion was “the opium of the people,” an obstacle to socialist progress. Atheism wasn’t incidental to communist totalitarianism; it was ideologically essential.

“That was scientific atheism, not atheism as such.”

This concedes the point. There was indeed a substantive form of atheism—scientific atheism—that made positive metaphysical claims and had catastrophic consequences.

But “scientific atheism” was just atheism combined with its natural philosophical partners: materialism, naturalism, scientism. These weren’t arbitrary additions. They were the commitments that made atheism intellectually coherent and practically significant.

Bertrand Russell defended naturalism and materialism. Richard Dawkins argues for evolutionary naturalism. Daniel Dennett defends materialism about consciousness. Sam Harris advocates a “scientific” approach to ethics. The connection between atheism and scientific materialism isn’t an aberration; it’s the standard package.

Contemporary atheists want to strip atheism down to bare “lack of belief” to separate it from these commitments. But this separation is artificial and historically dishonest. When atheism achieved power, it consistently allied with materialism and sought to eliminate religion.

“You can’t judge atheism by its worst adherents.”

We’re not judging atheism by fringe extremists. We’re examining how atheism functioned when it achieved institutional power and was implemented by its own strongest advocates. The Soviet Union made atheism central to its identity and produced extensive theoretical literature defending it. Albania enacted precisely what its leaders believed atheism required.

If Christianity is judged by the Crusades—and it is—then atheism must be judged by Soviet scientific atheism. These weren’t marginal examples. They represent the most extensive attempts to build explicitly atheist societies in human history.

The Function of the Redefinition

By defining atheism as mere “lack of belief,” contemporary atheists achieve five rhetorical victories:

Burden of proof is evaded: “I make no claims, so I prove nothing”

Philosophical commitments are concealed: “Atheism says nothing about materialism or naturalism”

Historical responsibility is denied: “20th-century regimes have nothing to do with atheism as such”

Atheism is presented as neutral default: “It’s just absence of belief”

Criticism is deflected: “You can’t criticize something that makes no claims”

But when Russell wrote “Why I Am Not a Christian,” he didn’t merely describe absence of belief. He argued for materialism and naturalism. When Dawkins wrote The God Delusion, he argued for scientific materialism. When Harris wrote The End of Faith, he advocated a comprehensive secular worldview.

This is atheism as it actually functions: a substantive metaphysical position with implications for reality, knowledge, and value. The 20th century shows what happens when that position gains power. Contemporary atheists who adopt the minimal definition want the benefits of atheism—rejection of religious authority, embrace of materialism, secular ethics—while denying atheism entails these commitments.

That’s intellectually dishonest. It lets atheists argue like metaphysical naturalists while claiming immunity from criticism because they “have no position.”

Conclusion

The “lack of belief” definition isn’t clarification. It’s obfuscation. It’s not neutral description. It’s strategic rebranding.

And it serves, above all else, to shield contemporary atheism from historical accountability.

When Albania closed all 2,169 religious buildings, when the Soviet Union killed 200,000 clergy, when Cambodia massacred 50,000 monks and destroyed 95% of temples, when China obliterated hundreds of thousands of temples—these weren’t accidents. These were explicitly atheist regimes acting on their understanding of what atheism entailed.

Contemporary atheists claim this history is irrelevant because atheism “just means lack of belief.” But the architects of these regimes said otherwise. They codified atheism in law. They taught it in mandatory curriculum. They propagated it through official institutions. And they documented what they meant: atheism as comprehensive scientific-materialist worldview, opposed to religion as false and harmful.

You can’t define away history. The blood of millions and the ruins of thousands of religious buildings stand as testimony to what atheism meant when it achieved power. Contemporary atheists who insist “that wasn’t real atheism” are engaged in historical revisionism—rewriting their own past to make it more palatable.

An honest atheism must acknowledge what atheism has meant historically, what it entailed when institutionalized politically, and what commitments typically accompany the denial of God. The 20th century cannot be dismissed by definitional sleight of hand.

The great dissociation—the attempt to separate contemporary atheism from its political embodiments—fails. Not because we lack evidence, but because we have too much of it. Documented. Verified. Undeniable.

Key References

Acton Institute (2008). The church and the terror state. https://www.acton.org/pub/commentary/2008/12/10/church-and-terror-state

Aegis Trust (2020). Cambodia. https://www.aegistrust.org/learn/mass-atrocities/cambodia/

Balkan Insight (2019). How Albania became the world’s first atheist country. https://balkaninsight.com/2019/08/28/how-albania-became-the-worlds-first-atheist-country/

Christian History Magazine (n.d.). Persecution and resilience. https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/ch-146-persecution-and-resilience

EBSCO Research Starters (n.d.). Stalin suppresses the Russian Orthodox Church. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/stalin-suppresses-russian-orthodox-church

Facts and Details (n.d.). Religion in Cambodia. https://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/cambodia/sub5_2e/entry-2879.html

Irreligion in Albania (2024). https://grokipedia.com/page/Irreligion_in_Albania

Karataş, İ. (2020). ‘State-sponsored atheism: The case of Albania during the Enver Hoxha Era’, Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe, 40(6).

ONE Magazine (2024). The long Good Friday of Albanian Christians. https://cnewa.org/magazine/the-long-good-friday-of-albanian-christians-30360/

University of Notre Dame (n.d.). China’s religious awakening after Mao. https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/chinas-religious-awakening-after-mao/

Wikipedia (2024b). USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USSR_anti-religious_campaign_%281958%E2%80%931964%29

Wikipedia (2024d). Persecution of Christians in the Eastern Bloc. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_Christians_in_the_Eastern_Bloc

Wikipedia (2024e). Religion in the Soviet Union. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_the_Soviet_Union

Wikipedia (2024f). Religion in Albania. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Albania

Wikipedia (2024h). Cambodian genocide. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide

Wikipedia (2024i). Buddhism in Cambodia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_in_Cambodia

Wikipedia (2024j). Antireligious campaigns in China. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antireligious_campaigns_in_China

Wikipedia (2024k). Cultural Revolution. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution