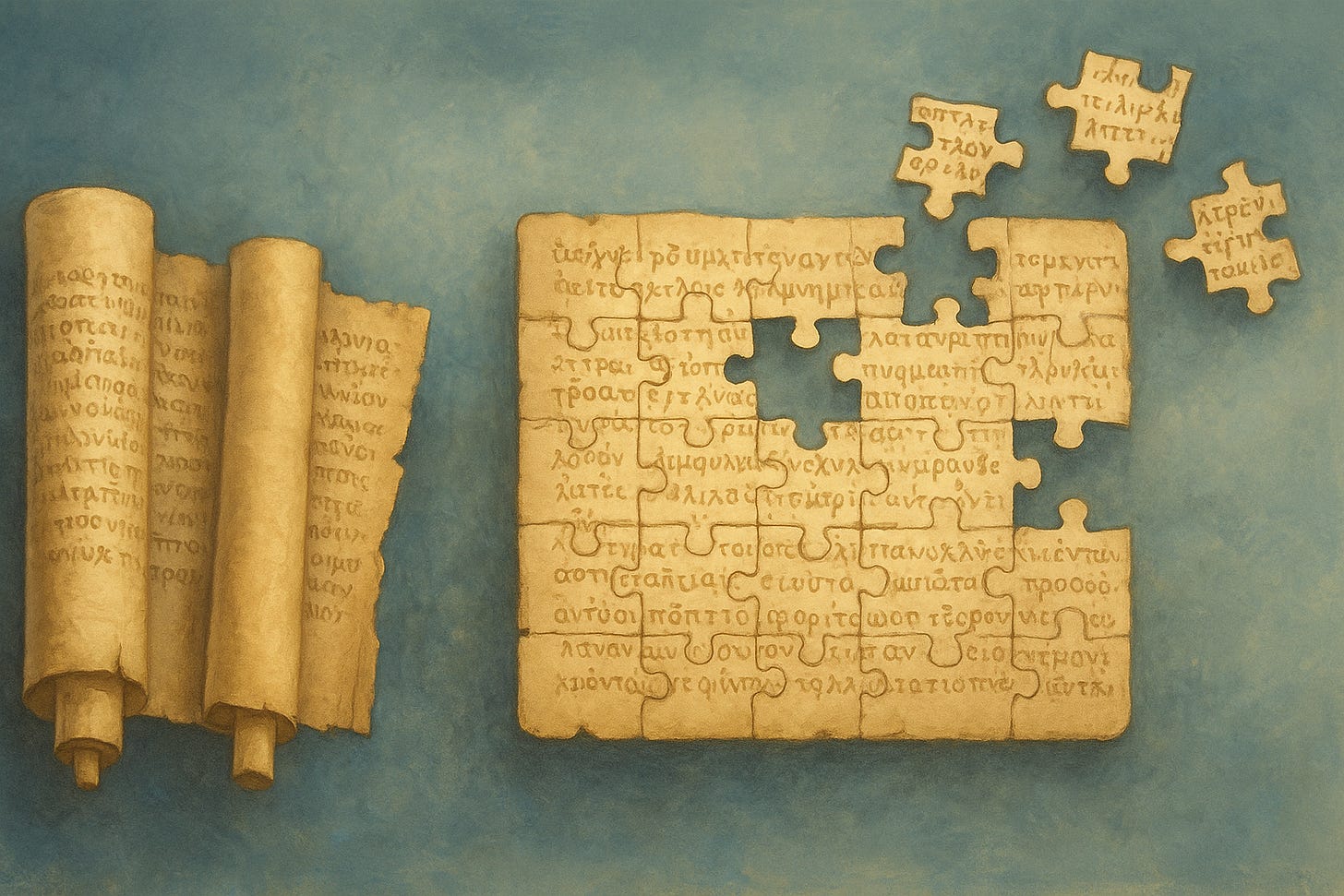

Preservation Through Multiplicity: The Puzzle With Extra Pieces

Contextualizing Biblical criticism and a defense for skeptical attacks

Introduction

“We don’t even know what the original New Testament said.” This claim appears frequently in popular skepticism about Christianity, often accompanied by statistics about textual variants: 400,000 variations across manuscripts, more variants than words in the New Testament itself. The implication is clear: the text has been corrupted beyond recovery, and with it, any confidence in Christian doctrine.

The argument is superficially compelling. But it misunderstands what textual variants actually represent and how the manuscript tradition actually works.

The New Testament doesn’t suffer from missing puzzle pieces. It contains the complete picture, plus hundreds of duplicate pieces that need to be identified and set aside.

This distinction matters. The over-preservation of the text through massive manuscript replication created detectability, not corruption. Where ancient works typically survive in handfuls of copies separated by centuries, the New Testament exists in thousands of manuscripts from multiple independent regions, many within a century or two of composition.

This abundance generates variants through the mechanics of hand-copying, but it also makes the original text more recoverable, not less.

This article examines what textual criticism actually reveals about the New Testament: early canonical stability, transparent transmission, and remarkable doctrinal robustness across all manuscript traditions. The evidence, evaluated historically rather than polemically, supports preservation through multiplicity.

Canon vs. Text: A Necessary Distinction

Discussions of New Testament reliability often conflate two separate questions: which books belong in the canon, and what are the exact words of those books. The first is a question of boundaries; the second is a question of precision within those boundaries.

The Canon Question

The core of the New Testament canon achieved recognition remarkably early. The four Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, and 1 John appear consistently across second-century sources.

Regional churches discussed seven books (Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 2-3 John, Jude, Revelation) without this producing doctrinal divergence. These “disputed books” (antilegomena) weren’t rejected; they simply took longer to achieve universal acceptance.

Importantly, the early church recognized rather than invented this canon. The books that became canonical were already circulating, already being read in worship, already being cited as authoritative. The formal canonization process acknowledged what was already functioning as scripture in the Christian community.

The Text Question

The text question operates entirely within the canonical boundaries. Given that we accept, for instance, that the Gospel of John is canonical, what exactly did John write? This is where manuscript variants enter the picture.

Ancient texts were copied by hand, creating inevitable variations. A scribe might skip a line, harmonize parallel passages, smooth grammar, or incorporate a marginal note into the main text. These variations accumulated as manuscripts were copied and recopied over centuries.

But crucially, the variations are detectable precisely because we have so many manuscripts to compare.

The early church was already aware of textual variation. Origen in the third century noted differences between manuscripts and attempted to determine original readings. This wasn’t a problem discovered by modern skeptics; it was a known feature of textual transmission that the church addressed openly.

The Theological Framework: Testing and Stewardship

Before examining the specifics of textual variants, we need to establish the theological lens through which Christians should view this evidence. Paul’s instruction to the Thessalonians provides the principle: “Do not treat prophecies with contempt but test them all; hold on to what is good” (1 Thessalonians 5:20-21).

This isn’t a call to credulity or defensiveness. It’s a call to discernment. The early church was commanded to test teachings, evaluate claims, and retain what proved true. This principle applies directly to textual criticism: we examine the manuscript evidence, we test the readings, we determine what is original, and we preserve what is good.

The Holy Spirit’s stewardship of Scripture doesn’t require miraculous scribal perfection or the elimination of human involvement. Instead, it works through the ordinary means of Christian communities copying, comparing, correcting, and transmitting texts across time and geography.

The Spirit preserves truth through human faithfulness and through the detectability that comes from abundant witnesses.

The absence of original manuscripts may itself reflect divine wisdom. Had the autographs survived, they would likely have become objects of veneration, potential distractions from the actual object of Christian worship: Jesus himself.

This concern isn’t merely theoretical. Even with ordinary copied manuscripts, some Christians fall into the error of venerating the text itself rather than the God it reveals. The tendency to treat Bibles as sacred objects rather than witnesses to Christ already creates theological confusion. Had original manuscripts survived, this problem would have intensified dramatically, likely producing a category of holy relics that would have obscured the very message they contained.

The multiplication of copies across regions and languages prevented any single physical object from becoming a focus of misplaced devotion while ensuring the message remained accessible and recoverable.

This explains the pattern we actually see: not perfect manuscripts immune to copying errors, but a transparent tradition where variations are visible and recoverable. The church has always known about textual questions and has always applied careful study to resolve them. This isn’t a failure of preservation but its mechanism.

The multiplication of manuscripts across independent transmission lines creates the very redundancy that makes textual criticism possible. Where manuscripts agree (which is the vast majority), we have certainty. Where they differ, we have the tools to determine original readings. This is stewardship through abundance rather than fragility.

Understanding this framework prevents two opposite errors. The first error treats any variant as evidence of corruption, assuming preservation required perfection. The second error assumes skeptical conclusions about variants without examining what they actually affect.

Both fail to test the evidence. The proper approach examines the manuscript tradition honestly, applies established text-critical methods, and evaluates whether variants affect the truth Christians are called to preserve.

Why the New Testament Has So Many Variants

The statistic about 400,000 textual variants sounds alarming until you understand what creates variants and what they actually represent.

The New Testament has more variants than any other ancient text for a simple reason: it has vastly more manuscripts. We possess over 5,800 Greek manuscripts, plus thousands more in Latin, Coptic, Syriac, and other early translations.

Most ancient works survive in a handful of copies. Homer’s Iliad, considered well-attested, exists in fewer than 2,000 manuscripts. For most classical texts, we have single-digit manuscript counts.

More manuscripts mean more opportunities to detect copying variations. If we had only one manuscript of the New Testament, we would have zero variants. If we had two manuscripts, we might have hundreds. With thousands of manuscripts spanning different times, regions, and copying traditions, we can identify every minor variation that emerged over centuries of transmission.

This is a feature, not a bug. Multiplicity creates transparency. We can trace how variants arose, where they spread, and which readings are original. The variants aren’t mysteries; they’re data points that allow reconstruction of the text’s transmission history.

What Variants Actually Look Like

The vast majority of variants are trivial:

Spelling differences (movable nu, itacism in Greek)

Word order changes that don’t affect meaning (Greek allows flexible word order)

Obvious scribal errors (repeated lines, skipped lines, transposed letters)

Minor grammatical smoothing

These account for the overwhelming bulk of the 400,000 variants. They’re significant for mapping manuscript relationships and transmission patterns, but they don’t affect translation or meaning.

The category of “meaningful and viable” variants (those that both make a difference to meaning and have reasonable manuscript support) is remarkably small. Most involve minor clarifications, harmonizations, or explanatory additions that later scribes made and that textual criticism can readily identify as secondary.

Early Witnesses to Textual Stability

Beyond the manuscripts themselves, we have additional evidence for the early stability of the New Testament text.

Second-century Christian writers quote extensively from the New Testament. Ignatius of Antioch (around 110 AD), Polycarp (around 130 AD), Justin Martyr (around 150 AD), and Irenaeus (around 180 AD) all cite Gospel passages and Paul’s letters in ways that match our earliest manuscripts. These quotations provide independent verification that the texts circulating in the second century correspond to the texts we possess today.

Early translations offer another line of evidence. By the third century, the New Testament had been translated into Old Latin, Syriac, and Coptic. These translation traditions developed independently from the Greek manuscript families, yet they witness to substantially the same text. When multiple language traditions preserve the same readings, it confirms that those readings were established early and widely.

These witnesses demonstrate that the text wasn’t fluid or evolving significantly after the apostolic period. The independent attestation from citations and translations, combined with the manuscript evidence, creates a web of mutually reinforcing testimony to textual stability.

The Major Interpolations

Several longer passages appear in some manuscripts but not others, representing the most significant textual questions. A survey of these demonstrates both the transparency of textual criticism and the doctrinal robustness of the tradition.

Mark 16:9-20 (The Longer Ending)

The earliest and best manuscripts of Mark end at 16:8 with the women fleeing the empty tomb in fear. Verses 9-20, which appear in later manuscripts, provide resurrection appearances and the Great Commission.

External evidence (manuscript testimony) and internal evidence (vocabulary and style differences) indicate this ending was added by later scribes to provide a more complete conclusion.

Doctrinally, this changes nothing. The resurrection is attested in all four Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s letters. The Great Commission appears in Matthew 28 and Luke 24. No doctrine depends on Mark 16:9-20.

John 7:53-8:11 (The Woman Caught in Adultery)

This passage about Jesus and the woman caught in adultery doesn’t appear in the earliest manuscripts and shows stylistic differences from John’s usual writing. It floats between different locations in various manuscripts.

Despite its beauty and its consistency with Jesus’ character elsewhere, it was likely a true story about Jesus that was preserved orally and later inserted into John’s Gospel.

The passage teaches forgiveness and Jesus’ authority, both attested throughout the Gospels. Its secondary status doesn’t affect any doctrine.

1 John 5:7-8 (The Comma Johanneum)

The phrase “in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one” appears only in late Latin manuscripts and a handful of very late Greek manuscripts. It’s clearly a later addition, likely a marginal note explaining the Trinity that was incorporated into the text.

The Trinity doesn’t depend on this verse. John 1:1-18, John 14-16, Matthew 28:19, 2 Corinthians 13:14, and numerous other passages establish the doctrine through independent attestation.

Minor Interpolations

Several shorter additions appear in various manuscripts:

John 5:3b-4 (the angel troubling the pool)

Luke 22:43-44 (the angel strengthening Jesus)

Luke 23:34a (”Father, forgive them”)

Acts 8:37 (the Ethiopian’s confession)

Various doxologies and liturgical additions

Each can be evaluated on manuscript evidence and internal coherence. None affects core doctrine.

Where they’re genuine, they’re attested elsewhere. Where they’re secondary additions, they typically reflect early liturgical practice or pious clarification.

Doctrinal Robustness Across All Variants

Here’s the crucial point: no textual variant, major or minor, affects any central Christian doctrine. This isn’t wishful thinking; it’s demonstrable from the manuscript evidence itself.

Every major doctrine of historic Christianity has multiple independent attestations across different New Testament books and different textual traditions:

The deity of Christ: John 1:1-18, John 20:28, Philippians 2:5-11, Colossians 1:15-20, Hebrews 1:1-3, Titus 2:13. No significant variants in these passages.

The resurrection: All four Gospels (multiple independent traditions), Acts, 1 Corinthians 15, 1 Peter, Revelation. The resurrection is attested even if you removed every disputed passage.

Salvation by grace through faith: Romans 3-5, Ephesians 2:8-10, Galatians, Titus 3:4-7. The doctrine is redundantly established.

The Trinity: Matthew 28:19, 2 Corinthians 13:14, John 14-17 (the Father-Son relationship and the Spirit’s role). Remove the Comma Johanneum and the doctrine stands unchanged.

This redundancy is what makes Christianity textually indestructible. The doctrines aren’t built on single verses but on interlocking testimonies from multiple authors working independently. Even radical text-critical skepticism (accepting only the earliest and most conservative readings) leaves Christian orthodoxy intact.

The Pattern of Preservation

When you step back from individual variants and look at the overall pattern, what you see is stewardship, not chaos.

Multiple independent manuscript families (Alexandrian, Western, Byzantine, etc.) preserve the text through different transmission streams. These families can be compared against each other, allowing reconstruction of earlier forms. Where they agree, we have certainty. Where they differ, we can usually determine which reading is original through established text-critical methods.

The early Christians took manuscript preservation seriously. They copied texts carefully, compared manuscripts, noted variations, and passed on both the texts and awareness of textual questions. This isn’t the behavior of people manipulating a message; it’s the behavior of communities stewarding something they believed was true and important.

The multiplicity itself suggests providential design, though not in the way people sometimes imagine. God didn’t preserve the text through miraculous scribal perfection. He preserved it through abundance: so many manuscripts, across so many regions, in so many languages, that the original text remains recoverable despite inevitable human copying errors.

Responding to Common Objections

“We don’t know what the original said.” This is demonstrably false for the vast majority of the New Testament. We know what the original said with extremely high confidence. The uncertain portions are well-identified and affect no doctrine.

“The church altered the text to support its theology.” This contradicts the manuscript evidence. The independent manuscript lines preserve texts that hadn’t been harmonized or systematized. If the church had successfully altered the text, we wouldn’t see the variations we do see.

“Doctrines were invented and then written into manuscripts.” Show me which doctrine depends on a disputed reading. You can’t, because the redundancy of doctrinal attestation means no single variant is theologically load-bearing.

“Textual criticism proves the Bible is unreliable.” Textual criticism proves transparency. The variations are visible precisely because we have the manuscript evidence to detect them. Reliability comes from this transparency, not from pretending variations don’t exist.

Conclusion

The New Testament manuscript tradition reveals remarkable preservation through an unusual mechanism: massive replication creating detectable variation within stable content.

The canon was recognized early. The text was transmitted openly with awareness of variations. The doctrines were redundantly attested across multiple independent sources.

This is the puzzle with extra pieces. The complete picture has been preserved. The textual critic’s job is identifying which pieces are duplicates, a task made possible by the very abundance that created the variations in the first place.

The pattern aligns with the biblical principle of testing and stewardship. The early church was instructed to test everything and hold fast to what is good, not to treat prophecies with contempt or to accept claims without examination. The manuscript tradition reflects this approach: texts were copied carefully, variations were noted, readings were compared, and the church exercised discernment about what was original.

The Holy Spirit’s preservation worked through these ordinary means. Not through miraculous elimination of human copying errors, but through the multiplication of witnesses across independent transmission lines, creating a transparent tradition where the original text remains recoverable.

This is stewardship through abundance and detectability rather than through fragile perfection.

The skeptical argument depends on treating textual variants as evidence of corruption when they’re actually evidence of preservation. The variations exist because Christians copied the text obsessively, not carelessly. They can be studied because the manuscript tradition is transparent, not because it’s been lost or manipulated.

Evaluated historically rather than polemically, the evidence aligns with providential stewardship: truth preserved through human means, in human contexts, by communities that valued accuracy precisely because they believed what they were copying mattered.

The church tested the manuscripts, compared the readings, and preserved what was good. The result is a text that is stable, a canon that is reliable, and doctrines that are intact.

The variations are real and visible, but they demonstrate the robustness of the tradition rather than its fragility. This is what the manuscript evidence actually shows when examined according to the principle we were given: test everything, hold fast to what is good.

Field Guide: Common Attack Vectors and Responses

Attack: “It’s like a game of telephone - the message got corrupted through copying.”

Why it’s compelling: Everyone has experienced how messages degrade through repeated oral transmission.

The actual issue: This analogy fails because manuscripts aren’t sequential. Each copy can be checked against others, creating a web of witnesses rather than a linear chain. We can compare thousands of independent transmission lines and work backward to reconstruct the original.

Response approach: “The telephone game analogy assumes sequential copying with no cross-checking. The manuscript tradition is more like having recordings from multiple phones in the room - you can compare them to recover what was actually said. When you have thousands of manuscripts from different regions and time periods, variations become detectable rather than compounding.”

Attack: “There are 400,000 variants - more than words in the New Testament!”

Why it’s compelling: The raw number sounds overwhelming and suggests chaos.

The actual issue: This statistic counts every difference in every manuscript. If ten manuscripts all have the same spelling error, that’s counted as ten variants. Most are trivial (spelling, word order, obvious errors).

Response approach: “More manuscripts create more variants because we can detect more differences. The Iliad has good manuscript support and still has significant variants. The New Testament’s variant count reflects its manuscript abundance, not textual instability. The meaningful variants that actually affect interpretation are a tiny fraction, and none affect core doctrine.”

Attack: “The church decided what books were scripture - they could have chosen anything.”

Why it’s compelling: Suggests arbitrary power and potential manipulation.

The actual issue: The church recognized books that were already functioning as scripture, not selected them from a buffet of equal options. The core canon was established by apostolic origin, early usage, and theological consistency.

Response approach: “The canonical books were already circulating and being used authoritatively before any formal councils. The councils recognized what was already accepted, similar to how a dictionary records how language is used rather than inventing it. The disputed books were few, and the discussions left no doctrinal gaps.”

Attack: “Constantine changed the Bible at Nicea to support his political agenda.”

Why it’s compelling: Conspiracy theories about power and manipulation are inherently interesting.

The actual issue: The Council of Nicea (325 AD) addressed Christology, not the canon. We have manuscripts predating Constantine that contain the texts we use today. The canonical lists that emerged later simply recognized earlier practice.

Response approach: “Nicea dealt with the Trinity, not the canon. We have manuscripts from before Constantine that contain the Gospels and Paul’s letters. The claim requires ignoring the manuscript evidence we actually possess. Constantine didn’t have the power to retroactively alter manuscripts already spread across multiple regions and languages.”

Attack: “Books were banned and burned - we’re missing the real story.”

Why it’s compelling: Suggests suppression of uncomfortable truths.

The actual issue: Late texts like the Gospel of Thomas were not “banned” - they were recognized as secondary works not from the apostolic period. Early Christians were aware of them and explained why they weren’t considered authoritative.

Response approach: “Second and third-century Christians had access to these texts and explained why they weren’t apostolic. The ‘banned books’ claim assumes the church successfully destroyed texts that we currently possess and can read. If the suppression failed this badly, why trust the conspiracy theory at all? These texts are available; read them and see why early Christians found them unpersuasive.”

Attack: “We don’t have the originals, so we can’t know what they said.”

Why it’s compelling: Seems logically airtight - no originals means no certainty.

The actual issue: We don’t have the original of any ancient text, but we can reconstruct them through manuscript comparison with high confidence. The New Testament is better attested than any other ancient work.

Response approach: “We don’t have Caesar’s original Gallic Wars either, but no one doubts we know what he wrote. The New Testament has far more manuscript evidence, far earlier, and far more widely distributed than any comparable ancient text. The lack of originals is true for all ancient literature, but the New Testament has better attestation than any of them. Theologically, the absence of originals may reflect divine wisdom: had the autographs survived, they would likely have become objects of veneration rather than tools for understanding. God preserved the message through abundant copies across regions and languages, preventing any single object from becoming a distraction from Christ himself.”

Attack: “Different manuscripts say different things - which Bible is the real one?”

Why it’s compelling: Suggests uncertainty about basic content.

The actual issue: Modern translations are based on critical editions that evaluate all manuscripts. The differences between manuscript families affect translation choices in minor ways but don’t create different messages.

Response approach: “Modern translations compare all available manuscripts and indicate significant variants in footnotes. The differences between Greek texts used by various translations are minor and affect no doctrine. You can compare translations and see they tell the same story, teach the same truths, and present the same Christ. The variants are transparent, not hidden.”

Attack: “Scribes were biased - they changed the text to support their theology.”

Why it’s compelling: Assumes motivated reasoning and dishonesty.

The actual issue: If scribes systematically changed texts toward orthodoxy, we wouldn’t see the variation patterns we do see. Independent manuscript families preserve different readings, indicating that systematic theological tampering didn’t occur.

Response approach: “If scribes successfully altered texts toward a unified theology, we wouldn’t see the variations we see between manuscript families. The variations that exist are generally minor and don’t show systematic theological shaping. The transparency of the tradition argues against successful manipulation.”

Attack: “The ending of Mark was added - proves the text was corrupted.”

Why it’s compelling: A clear example of addition suggests broader unreliability.

The actual issue: This demonstrates the transparency of textual criticism. We can identify the addition because we have early manuscripts without it. This shows the method works.

Response approach: “The fact that we can identify the longer ending of Mark as secondary proves textual criticism works. We’re not hiding it - it’s in the footnotes of most Bibles. And doctrinally, it adds nothing not found elsewhere. This is evidence of preservation and transparency, not corruption.”

Attack: “Scholars disagree about the text - shows it’s unreliable.”

Why it’s compelling: Disagreement suggests uncertainty.

The actual issue: Scholars debate a small number of readings where the manuscript evidence is genuinely balanced. They agree on the vast majority of the text and on the fact that no variants affect doctrine.

Response approach: “Scholars debate perhaps 1-2% of the text, and those debates are about minor details of wording, not major content. They unanimously agree that no textual variants affect any core Christian doctrine. Academic debate about details demonstrates rigor, not uncertainty about the essential message.”

General Tactical Principles

Apply the biblical principle of testing: The instruction to “test everything, hold fast to what is good” applies to manuscript evidence. Don’t treat variants with contempt or defensiveness. Examine them honestly and show what the testing reveals.

Acknowledge real facts: Don’t deny that variants exist or that some passages are disputed. Transparency strengthens credibility and reflects the Spirit’s stewardship through detectability rather than through hiding problems.

Shift from counting variants to evaluating impact: Move the conversation from raw numbers to actual doctrinal significance.

Use comparative context: The New Testament has better manuscript support than any other ancient text. If its attestation makes it unreliable, we know nothing about the ancient world.

Emphasize redundancy: No doctrine depends on disputed passages. Every major teaching has multiple independent attestations.

Point to transparency: The fact that we know about variants and discuss them openly demonstrates the integrity of the tradition and the Spirit’s preservation through abundance.

Avoid overstating: Don’t claim we have perfect certainty or that there are zero difficult questions. Measured honesty is more persuasive than defensive overconfidence.

The goal isn’t to “win” arguments but to demonstrate that the textual evidence, honestly evaluated according to the principle of testing and discernment, supports reliability rather than undermining it. The church has always known to test the manuscripts and hold fast to what is good. That testing reveals a stable, recoverable text.

In sum: The New Testament comes to us through abundant witnesses, not fragile perfection. The variants are visible because preservation worked, not because it failed. Test the evidence honestly, and what remains is a reliable text, a recognized canon, and doctrines intact across every manuscript tradition. This is what stewardship through multiplicity actually looks like.

James (JD) Longmire

ORCID: 0009-0009-1383-7698

Northrop Grumman Fellow (unaffiliated research)

Acknowledgment: The “puzzle with extra pieces” analogy originated with Wesley Huff, whose clear thinking about textual criticism has helped many understand what the manuscript evidence actually shows.